This winter I started posting about photography and how it relates to understanding/portraying history, because this is a topic I find particularly interesting. My

first post was an introduction to 19th century photographic processes and the ways in which they were used. Today I'm continuing that theme, but we're adding some new inventions to the mix!

At the same time the daguerreotype was probably the most popular form of photographic development, a different process was also making its way onto the scene. Invented by Frederick Scott Archer, the "wet-collodion" process in the late 1840s. Known as wet-plate photography, the wet-collodion process produced a clear, noiseless image with a much shorter required exposure time than any of the currently popular processes. Wet-plate images could also be copied an infinite number of times from a single negative. This made producing images for publication a possibility, and the shorter exposure time made wet-collodion the best option for candids and outdoor shots.

|

| "Head of the Harbor," Balaclava, Russia c.1855 by Roger Fenton |

The downside of the wet-collodion process was that it required the image to be developed almost immediately (i.e., while the exposure plate was still wet), or the integrity of the image would be greatly compromised. As a result, in order to shoot wet-plate photographs, photographers needed to travel with a portable dark room.

|

| photographer with his hand-made development tent for wet-collodion processing, c.1850s, via The JDL site |

|

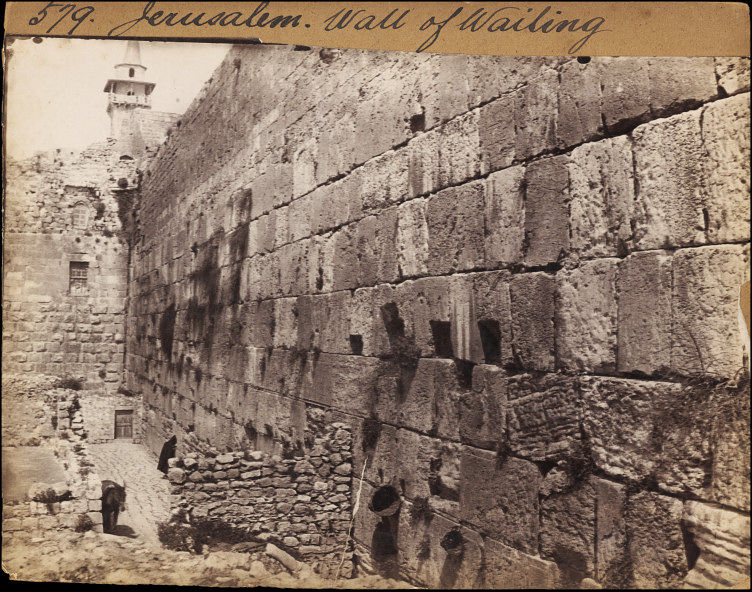

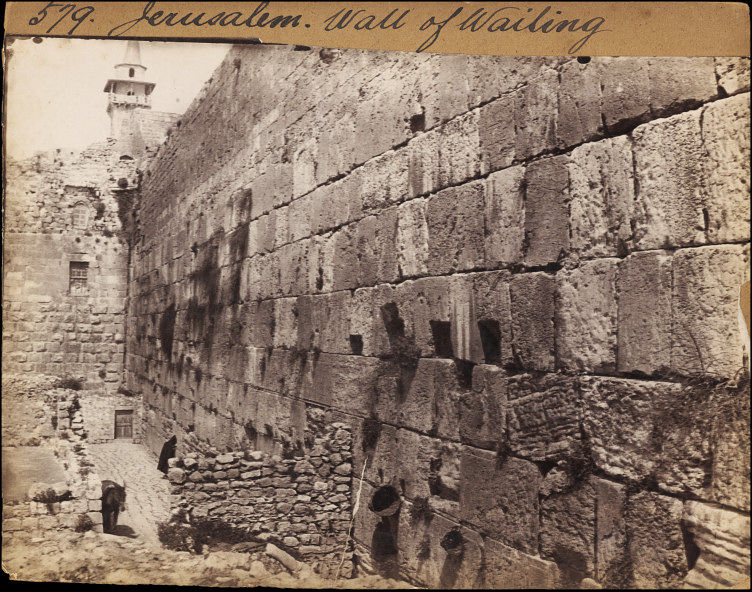

Still, wet-plate photography helped to start the "golden age of travel photography" [1] in the second half of the 19th century. These images gave everyday people, who could not afford to travel across the globe, a window into distant corners of the world.

|

| Western wall, Jerusalem, c. mid-19th century, by Francis Frith. (V&A collection) |

|

| Yosemite, American West, 1865, by Carleton Watkins (LoC) |

Faster, reproducible images were also perfect for another purpose: capturing the realities of war. Roger Fenton, who traveled to Russia in the 1850s, used wet-collodion processing and a specially-designed mobile darkroom to photograph the Crimean War. His images are a mix of fascinating and exotic uniforms, the generic chores of camp life, and the grim, stark realities of battle casualties. For the first time, people at home in England saw glimpses of battle, in shockingly realistic candid photographs from the field.

These images of battles and peoples in distant places were certainly new and stark and fascinating, but they had a sort of space guaranteed by the utter otherness of their subjects. In contrast, the photographs taken during the American Civil War were both honest in their portrayal of battle, but also brutal in their closeness.

Before the war, Mathew Brady had a photography studio in New York, and in the late 1850s was working with his partner Alexander Gardner to specialize in life-size portraits using enlargement techniques that were a cutting edge area of wet-plate photography. "Brady saw himself as a pictorial historian," and so when war broke out on home soil, Brady undertook to document it.

|

| company of 6th ME infantry after the Battle of Fredricksburg, 1862, by Mathew Brady (National Archives) |

Brady took--and exhibited at his gallery--graphic images of the war's front lines. As the war grew, so did Brady's coverage: at times he had up to 20 photographers in the field. The production of clear images, taken quickly with "the never-failing tube," that were reproducible for dissemination among the American public was a direct result of Brady's use of the wet-collodion process.

|

| Chaplain conducting mass for the 69th New York State Militia encamped at Fort Corcoran, DC, 1861 |

|

| casualties from the Battle of Antietam |

|

| Camp Northumberland, c.1860-65 |

Sources:

[1]

Global Views, 19th century travel photography in the Princeton Archives

[2] Lewinski, Jorge (1986). The Camera At War: War Photography for 1848 to the Present Day

No comments:

Post a Comment