Browsing posts, Pinterest boards, books, and articles about

historical costuming reveals a wide variety of sources we use as inspiration;

extant garments, paintings, fashion plates, and portraits are some of the most

common. This is true for a lot of periods (although the farther back you go

the more scarce extant garments become), because artists have been capturing

the human image for centuries and in general we like to be memorably captured

in our best clothes.

|

| throwback Thursday: getting captured in our best clothes by eminent "street style" photographer Bill Cunningham in 2012 |

But something revolutionary happened in the nineteenth

century: the process of using a mechanical device to capture an image and,

using chemicals and light, create a semi-permanent likeness was developed. In

other words, photography was invented. Depending on what you read, there are a

lot of dates and inventors associated with the photographic process, and to

this day both technology and artistic practices are constantly evolving and

experimenting and changing what photography means. This post is just a brief

overview, focusing on some highlights that interest me.

|

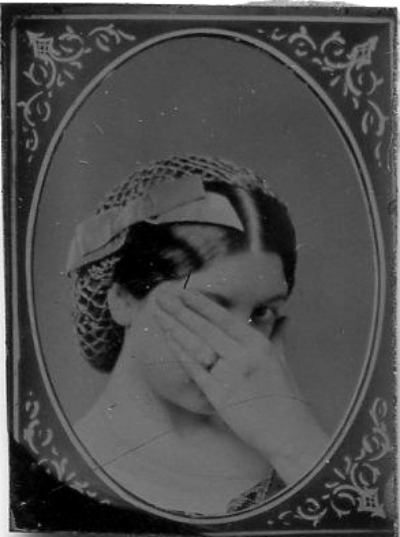

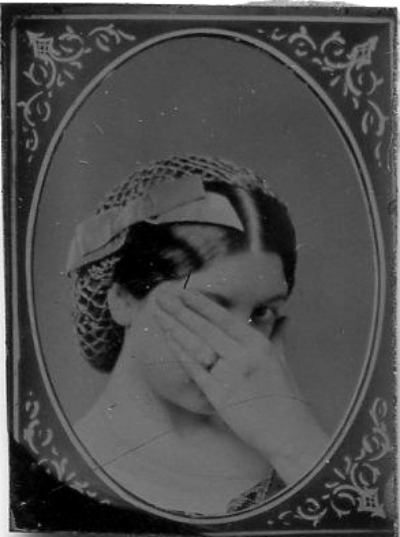

| 19th century tintype, source unknown |

|

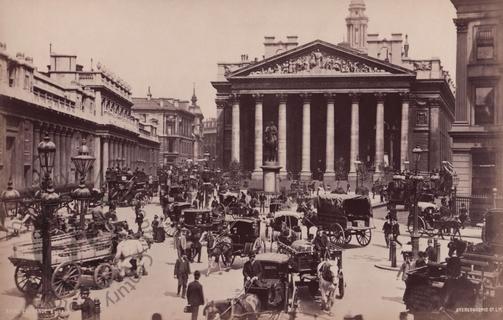

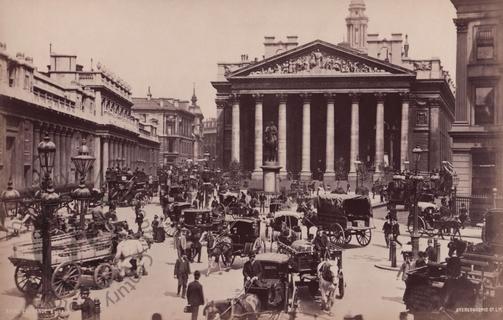

| The Royal Exchange, London, mid 19th c. by the London Stereoscopic Company |

There are two ways of looking at photography as a monumental

contribution to our understanding of history (and our ability to re-create it):

the subject and the photographer. Most obviously, photographs (or heliographs

or daguerreotypes or ambrotypes or tintypes depending on the process used) are

taken of something. This allows us, the modern viewer, to see whatever it was

that the photographer saw when the image was taken. It might be what our street

looked like in the 1860s, what a store might look like, or (of course) what

people looked like/wore. Looking at photographic likenesses (rather than

paintings or mass-produced illustrations like fashion plates) gives us a chance

to inspect details, step into the every day, and witness historic moments.

|

| Mass Ave, Cambridge (right near my house!), mid 19th century, via the Cambridge Public Library Archives |

|

| Harvard students at play, 1909, via the Cambridge Public Library Archives |

The second way that I find photographs so important for

history is what they tell us about the person who took them. In many cases

(e.g., studio portraits, journalistic photos), producing images was a trade

much the way it is today. But (also like today) photography was also a form of

artistic expression, world exploration, and documentation. While certainly

there are career photographer’s whose work is important for our understanding

of history, I am most fascinated by the world as it was captured by amateurs.

|

| photograph, 1862, by Viscountess Hawarden |

|

| children playing, Newcastle, 19th century, photographer unknown |

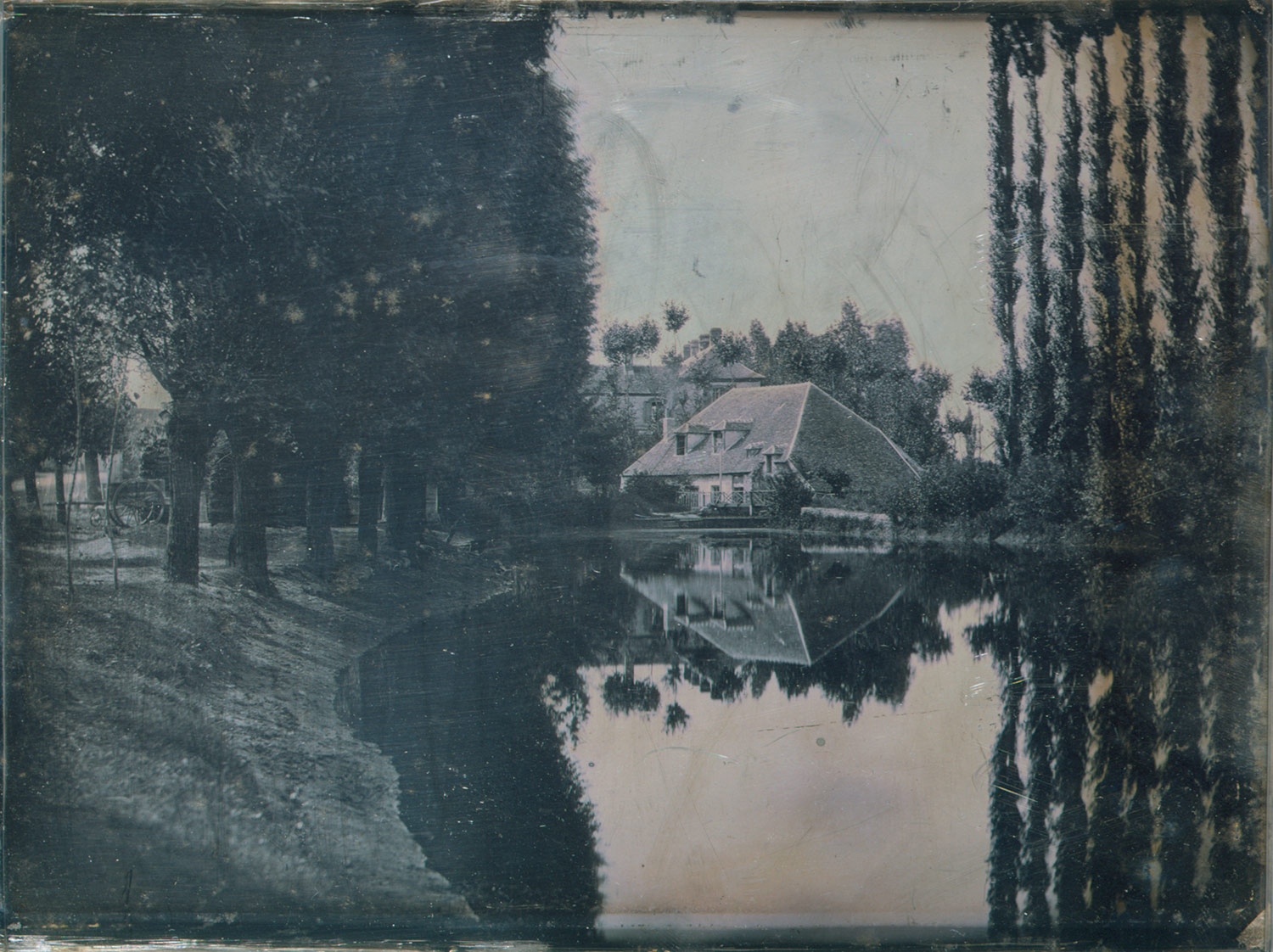

While the roots of modern photography go back as far as the

1810s, it wasn’t until the development of the daguerreotype—the first popular

photographic process, named for its inventor Louis Daguerre—and its refinements

in the 1840s that portraits could be done relatively easily and cheaply. For

the first time, taking a picture of someone or something had a relatively short

exposure time and produced a detailed, permanent image. Thanks to the French

government’s decision to put the Daguerre process in the public domain, the system

took off to capture portraits, scientific findings, astronomical views,

urbanization and modern architecture, archeological expeditions,

anthropological studies, and an array of artistic experiments over the course

of the next two decades.

|

| Salon of Baron Gros, daguerreotype, 1850s via the Met |

|

| Two nude women, stereoscopic daguerreotype, 1840s [also they have tiaras!] via the Met |

|

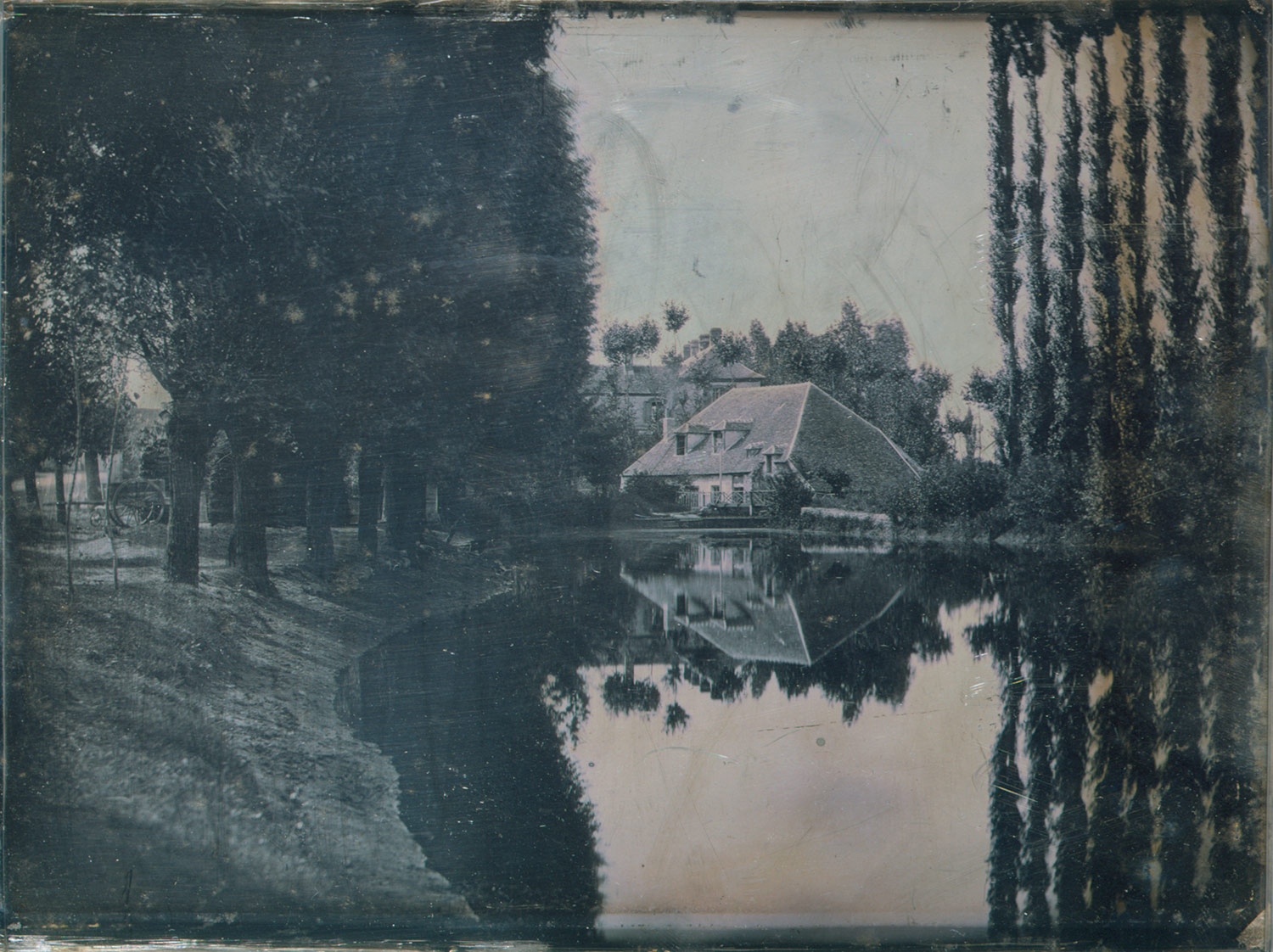

| Landscape with cottage, daguerreotype, 1847 via the Met |

The Daguerre process used copper plates coated with silver

nitrate that were then treated with iodine fumes, exposed to light in the

camera, and developed with mercury fumes before being “fixed” with hyposulphite

of soda. In the 1850s, the invention of Albumen paper by Louis Blanquart-Evrard

introduced the first paper photographic prints. Albumen was cheap, portable, and

could be purchased in lard quantities. This further aided the popularity of

both professional and amateur photography because while immediate development

of the image (and therefore an on-site darkroom) was still required, it made

the process cheaper for patrons, more approachable for photographers, and more

portable. While not quite as clear daguerreotypes, albumen photographs could

have multiple prints of a single image, and they were also much better for

pasting into photo albums. While the daguerreotype stayed popular in the US

into the early 1860s, albumen paper-printed photographs eventually overtook

them it.

|

| "Transporting the Bavaria Statue to Theresienwiese", Albumen print, 1850 |

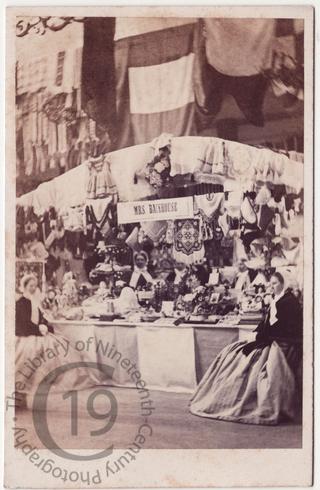

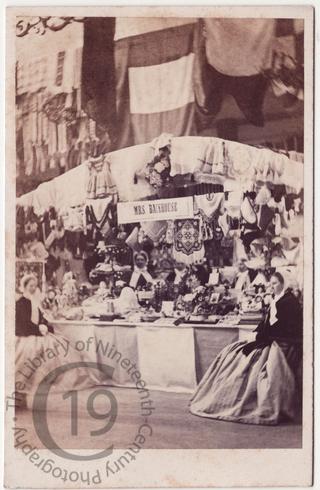

As the photographic process became faster, cheaper, and

easier over the second half of the 19th century, likenesses became a

much larger part of everyday life. New technologies developed better lenses and

smaller cameras, while new chemical approaches changed development.

Stereoscopic images brought pictures into 3 dimensions. Births, deaths,

marriages, and lazy summer afternoons were documented for posterity. Fabulous

clothes were captured. We can see many of these images today in archives and

online, which is a really neat way to jump into the past.

So I will leave you with a quote to think about, and some

images to inspire you. What photographs have shaped your vision of the past? Do

you like using them for research?

“Photography transcends the bounds of time and space. It

enables you to see at great distances things that you could never see, to know

things that you could never know, to see events that have passed and no longer

exist. “ Grant Romer, PBS

|

| unidentified couple on stilts |

|

| Expedition to Egypt, 1850 |

|

| portable portrait studio, Ireland, c.1870 |

|

| c.1870 |

|

| Bazaar stall, 1867 |

Read more about the birth of modern photography:

No comments:

Post a Comment