This post goes back a bit to our

suffrage tea in September, but it's baking-related, so if you feel like adding a 1915 twist to your holiday baking, it still applies!

For the suffrage tea I made a recipe from

Suffrage Cookbook, published in 1915 by the Equal Franchise Federation of Western Pennsylvania, called "marshmallow teacakes." This recipe intrigued me for a few reasons: first, it's from a suffrage cookbook, but it also uses some spiffy new popular tech from the 1910s--prepared foods.

|

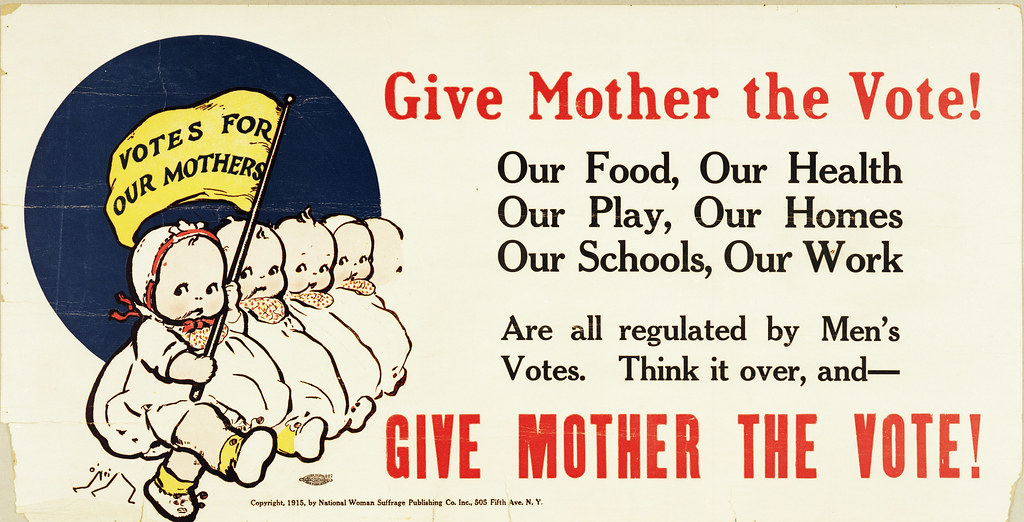

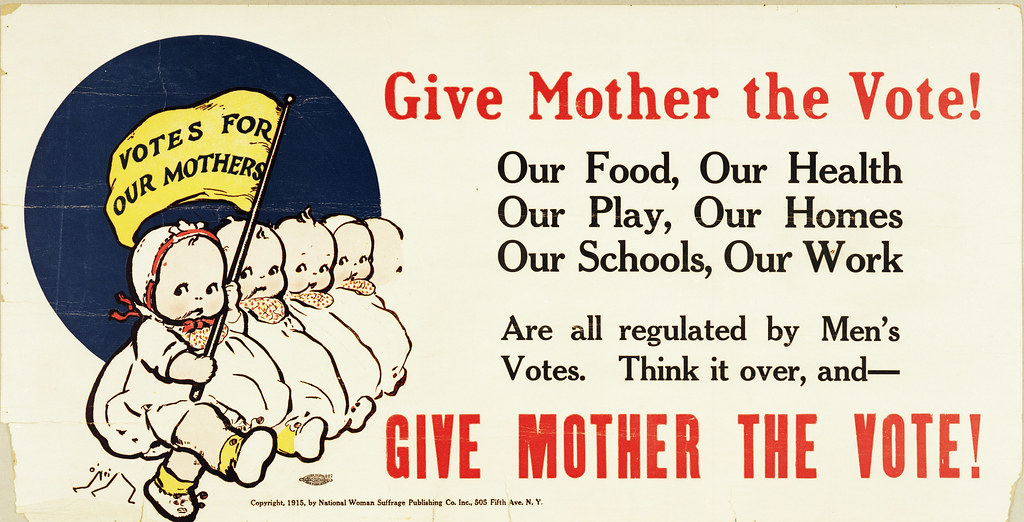

| a domestically-focused suffrage poster, 1915 |

Suffrage cookbooks were produced throughout the United States from the 19th century through the 1910s to raise funds, share ideas, and promote community within the suffrage movement. Cookbooks also helped strengthen the idea that women were masters of the domestic sphere, and therefore deserved the vote to be able to participate in politics (which affect domestic life) while countering the depiction of voting women as neglectful of traditional female tasks (like cooking). Diverse contributions to such cookbooks promoted varied representation for women from all walks of life fighting for the right to vote--as well as gave them a chance to network and advertise for their cause.

|

| Cover of the first suffrage cookbook, 1886 |

In addition to supporting the image of voting women as still domestic and providing a perfect fundraiser, suffrage cookbooks also provided an avenue for exchange--leading to possibly my favorite parts of the cookbooks. First, each book lists its contributors. To modern eyes these lists range from a "who's who" of the suffrage movement (the book pictured above features contributions from Lucy Stone and Alice Stone Blackwell, for example) to complete unknowns. Cookbooks were an equalizing platform--women who wouldn't get up and give great speeches at a rally could still show their support by submitting a recipe. Second, women (and a few men) didn't stop at recipes; they also submitted useful remedies, inspiring quotes, and satirical pieces. The 1886

Woman Suffrage Cookbook published in Boston includes a section called "Eminent Opinions on Woman Suffrage" along with sections on cakes, sauces, and meat preparation.

My recipe comes from a more contemporary cookbook for 1915, our year of choice for the September rally (it's really been less than 100 years since women could vote). In addition to popular recipes for the early 20th century, it includes two truly fabulous satirical pieces: "Pie for a Suffragist's Doubting Husband" and "Anti's Favorite Hash." To give you a taste (pun intended...) here's the latter:

"Anti's Favorite Hash

(Unless you wear dark glasses you cannot make a success of Anti's Favorite Hash.)

1 lb. truth thoroughly mangled

1 generous handful of injustice.

(Sprinkle over everything in the pan)

1 tumbler acetic acid (well shaken) |

A little vitriol will add a delightful tang and a string of nonsense should be dropped in at the last as if by accident.

Stir all together with a sharp knife because some of the tid bits will be tough propositions."

|

| cover of the 1915 cookbook |

I think this really captures what I think is so interesting about these cookbooks. On the surface, they were in both in keeping with the common message (that women's domesticity was exactly

why they should have the vote) and counter to the "anti" side (that voting would stop women from completing their household duties)...but underneath they were a tool for organizing, for sharing words of encouragement, for venting frustration, and for furthering their political aims. Suffrage cookbooks were more than domestic fundraisers--they were a political act.

Which brings us to the recipe I chose. Here's the recipe from the book (which you can check out in full over at

Project Gutenberg):

"Marshmallow Teas

Arrange marshmallows on thin, unsweetened round crackers. Make a deep impression in center of each marshmallow, and in each cavity drop ¼ teaspoon butter. Bake until marshmallows spread and nearly cover crackers. After removing from oven insert half a candied cherry in each cavity.

These are excellent with afternoon tea."

|

tin for Blue Bird Marshmallows, early 1900s

|

Marshmallows were widely available as tinned treats in the early 1900s, and by 1915 were made using a very similar recipe to that used today (which uses gelatin for a more "stable" product). In fact, there was a local marshmallow and marshmallow creme factory in Melrose, which opened in 1913. The factory was run by Amory and Emma Curtis, a savvy brother/sister team. Emma was a businesswoman, with knack for marketing--she cultivated the image of herself as a kindly older lady with a gray bun, and became the face of "Miss Curtis' Marshmallow Creme." In 1915 the Curtis Marshmallow Company displayed at the Panama Pacific Exposition, where their marshmallow creme won a gold medal. The booth was staffed by women with gray buns--Emma Curtis's brand. So marshmallows are particularly apt for a Boston suffrage tea!

Similarly, candied cherries were also available for purchase in the 1910s. There isn't nearly as much information about their origin as a mass-produced item, but I found several patents for candied cherries from the period (such as this one for

Fort Snelling products in 1915), so I feel comfortable saying it's quite possible a modern woman might have had them on hand. Not to mention they were quite the popular ingredient in 1915--everything from

peach custard to

Christmas cake to

plain in a bowl--so the teacake recipe is a perfect period bite. I particularly like this description of candied cherries from the

Ohio Farmer: "No decoration for cake or other confection is more vivid that preserved and candied cherries."

|

| sheet music for the Candied Cherries Two-Step, 1911 (via) |

So with the three main ingredients picked up at the grocer, it would be easy to whip up some marshmallow teacakes after a day of picketing, singing, and speechifying for woman's right to vote!

|

| marshmallow teacakes at center front, at or suffrage rally and tea |

To make the marshmallow teacakes as instructed in

Suffrage Cookbook, I started with store-bought marshmallows and "old fashioned" tea biscuits. The original recipe calls for unsweetened crackers, but I couldn't find anything unsalted that went acceptably with marshmallows. After some experimenting, the basically-unsweetened tea biscuits were easily the best choice, not adding unneeded sweetness and solid enough to support the marshmallow during and after baking.

Next, I needed candied cherries...but I couldn't find any! It turns out most stores only sell them around Christmas, and trying to find them in September was a lost cause...so I had to cheat and make my own. They're not nearly as vibrant or well-shaped as manufactured ones, but they tasted just fine. (I picked up a bunch at the store for next time, but you can also order them online if you give yourself time.)

To be honest, these were a little too sweet for me, but they went over better than I expected at the tea (I mean, they're basically just marshmallows and cookies so what's not to like?), and I was pleased to add something so perfect for the occasion. Here's my final recipe--it's a bit different than the original, but I think the spirit remains.

Marshmallow Teas, adapted from

Suffrage Cookbook (1915):

standard-size marshmallows (on the small side is better than large)

tea biscuits (I used Nabisco Social Teas, but round* Rich Tea biscuits would be even better!)

candied cherries

Preheat oven to 200F.

With a small knife, hash one long side of each marshmallow so that the powdered coating is broken up, and the sticky inside can meet the biscuit, and make one hole in the opposite side (I cut a small "+"). Place each marshmallow on a tea biscuit, hashed side down. Bake for 2-3 minutes, or until marshmallow softens and begins to melt, attaching to the biscuit below. While marshmallows are still soft, place a candied cherry into the hole on the top side. Cool completely.

So easy you can do it and still have time to march!

|

| they're not the prettiest...but they tasted good! |

*if using round biscuits: eliminate the hashing, and cut the marshmallow in half the short way. Place the cut end of the marshmallow on the biscuit.

For more on suffrage cookbooks or Miss Curtis' Marshmallow Creme:

The Melrose Historical Society

"The Trojan Horse of Women Suffrage," Rare Books Digest

"How Suffragists Used Cookbooks as a Recipe for Subversion," NPR

"Hiding Spinach in the Brownies," Social Movement Studies

A list of suffrage cookbooks at the Old Girl Network

and weird but also related:

Somerville's

Fluff Festival, honoring the invention of Marshmallow Fluff (but they don't mention the Curtises)

Enjoy!