|

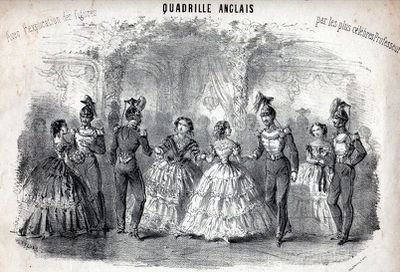

| a society ball in Paris, 1868, from Lunivers Illustre |

While abroad, the hotel where Amy and Aunt Carrol* are living is also home to several other Americans, and so the venue hosts a Christmas ball for the ex-pats. I'll let Alcott set the scene:

"she loved to dance, she felt that her foot was on her native heath in a ball-room, and enjoyed the delightful sense of power which comes when young girls first discover the new and lovely kingdom they are born to rule by virtue of beauty, youth, and womanhood. ...With the first burst of the band, Amy's color rose, her eyes began to sparkle, and her feet to tap the floor impatiently; for she danced well, and wanted Laurie to know it."

Quadrille, or Cotillon

"The set in which they found themselves was composed of English, and Amy was compelled to walk decorously through a cotillon, feeling all the while as if she could dance the Tarantula with a relish."

Quadrille, or Cotillon

"The set in which they found themselves was composed of English, and Amy was compelled to walk decorously through a cotillon, feeling all the while as if she could dance the Tarantula with a relish."

Amy and Laurie dance the first dance of the ball together (the aforementioned cotillon) while Amy is fit to bursting to do something more complicated where she can show off (we'll come back to that "tarantula" in a bit). That description leads me to believe that the cotillon Amy finds herself in is what I would refer to as a quadrille: a dance for 4 couples which includes multiple sections, is typically performed by walking through patterns, and was immensely popular throughout the 19th century. Here's a bit of the Prince Imperial quadrille as an example--the clip begins at the start of figure 3 of the dance, and ends at about 1:04 (and a ballroom, the figure would be repeated 3 more times).

Howe explains the terminology of cotillon vs. quadrille in his 1858 manual:

"Cotillions or cotillons are of English origin, Noah Webster** spells the word both ways. The word Cotillion was derived from the English, and the word Cotillon from the French. And were first danced by four persons standing as the first four now do, in the set; two more couples were afterwards added and formed the side couples; thus the English Cotillion and the French Quadrilles are now formed precisely alike, and it is equally proper to call the dance by either name."

"Cotillions or cotillons are of English origin, Noah Webster** spells the word both ways. The word Cotillion was derived from the English, and the word Cotillon from the French. And were first danced by four persons standing as the first four now do, in the set; two more couples were afterwards added and formed the side couples; thus the English Cotillion and the French Quadrilles are now formed precisely alike, and it is equally proper to call the dance by either name."

I am used to the term quadrille, so that's what we're going with. Let's break it down!

By the 1860s (and I think it's safe to say that Amy is in Europe between 1867-1870), a quadrille is done by 4 couples together in a square with 4 sides (so two couples face each other)-- this is called the set. Then within each set the couples are numbered 1-4, which determines the order in which you dance different figures:

|

| quadrille arrangement diagram, from Howe (1862). The first couple is always closest to the head of the hall, typically where the band is located. |

Often you dance with your partner as a couple, interacting with other couples. But sometimes you also dance as individuals: for example, ladies and gentlemen might do different things, or couples might split and dance with the person across the set from them. This second arrangement is also common, and is called "pairs":

|

| numbered pairs for quadrilles, Howe (1862) |

Something else you may have noticed: quadrilles are really long! There are multiple sections*** (usually, but not always, 5) in a quadrille, with separate distinct music for each section. Each section has its own sequence of patterns (called "figures") that the couples complete. Quadrilles tend to mirror other dance trends in the particular year of the quadrille's initial creation, as well as serving as an introduction of different steps that also become popular round dances (including several of the Bavarian dances I've mentioned in previous posts). So the typical breakdown of a quadrille in the late 1860s would include mostly walking, perhaps with the addition of some waltz, polka, or other round dance. Since Amy is internally complaining about walking, I think it's safe to assume this is an all-walking quadrille like the French Quadrille and Prince Imperial Quadrille videos above.

|

| illustration of figure 3 from the Lancers Quadrille, frontispiece for quadrille music c.1860 |

I actually also found a clip from the ball, and you can hear the arrangement! It goes from 6:48 to about 7:12 in the video (sharing is disabled, but you can watch it here if you're curious).

|

| This is a Lancers arrangement of music from Ruddigore, another G&S operetta I performed in |

As a final example, I have some terrible footage of a recent performance of the Prince Imperial Quadrille this September (there's a reason I'm not in charge of videography!). The reason I'm including it is to show two things: one, the way quadrilles move through different figures, and two, a bit of how it looks when you dance with a complete set of 4 couples. On the latter, notice how the two active couples complete 2 figures (forward and back, ladies' chain) then all 4 couples do a figure together (march to corners). The video cuts off just as we start march to corners.

Polka-redowa (3/4)

"She showed him her ball-book with demure satisfaction when he strolled, instead of rushing, up to claim her for the next, a glorious polka-redowa." -New Impressions

Fast forwarding a bit through the evening (although Alcott's ball descriptions are incredibly colorful and this one is the best...if it's been a while, I recommend going back and re-reading this whole chapter :) ), Amy finally gets to show Laurie what she can do when they dance a polka-redowa together. Does the word "redowa" and the time signature ring any bells? We're back in waltz time, and we talked about redowa when Meg danced it in The Laurence Boy.

Polka-redowa is another dance from the Bavarian fad, and is comprised of sliding steps, cutting steps, and leaping steps. This same list of steps is used in several of the Bavarian round dances, but the prevalence of leaps in the polka-redowa makes it especially elegant to watch when done well (and very exhausting). Because it is in 3/4 time (the same time signature as plain waltz, polka mazurka, and several other dances), it's possible to swap polka-redowa in and out with other steps. This helps mitigate the energy required for all the leaping because you can show off for a bit and then take a break with something lower-impact like plain waltz.

|

| the polka redowa illustration in Hillgrove (1863) |

1860s dance manuals describe this dance as being like the polka, except not. Seriously, Howe (1862) describes the polka-redowa as:

"This dance is composed of the same step as the Polka, with the exception that you slide the first step instead of springing, and omit the pause, as in this dance you count three, both for the music and dance."

So, do a polka step, but use a slide instead of a hop on the first step, and count in 3 rather than 4. How is that the same step as the polka? sigh. Several other manuals I looked at had similar descriptions, but Hillgrove's 1863 A complete practical guide to the art of dancing (another trusty favorite) gave us a bit more. He still describes the step as being a polka step, but adds some explanation of how the changes to polka-redowa impact its form:

"This dance is precisely the same as the first three movements of the Polka, the fourth step or interval berg omitted; and is danced in three-four time...which makes a more graceful and easy dance than the Polka, and one that is a great favorite."

Here the easy grace that is noticeable in well-executed polka-redowa is highlighted.

Below is an example of polka redowa, pulled from an 1860s waltz choreographed for performance--notice that even though a hop is used to turn 180 degrees each time, it's a pretty smooth dance.

Below is an example of polka redowa, pulled from an 1860s waltz choreographed for performance--notice that even though a hop is used to turn 180 degrees each time, it's a pretty smooth dance.

I think with this note about gracefulness in mind, polka-redowa is a perfect dance for Amy to really show her skills. It is difficult to execute well, and it requires stamina and form to make all the sliding and leaping look easy and elegant. Plus, the pointed toes that peak out when you slide your foot forward are a perfect opportunity for Amy's white satin slippers to make an appearance!

|

| white satin dancing shoes, mid-19th century (MFA collection). More on 1860s dancing shoes here. |

Hillgrove also notes that polka-redowa can be done in several different ways, and it's up to the gentleman to use whichever method he sees fit. This is an added challenge, because you really have to know the dance backwards and forwards!

"There is no particular rule by which the Polka Redowa should be performed. This is left to the option of the individual. It may be danced turning to the right or to the left, backward or forward; or, in cases where there is not sufficient space to proceed, the step and portion may be preserved in making a kind of balance or set."

This is also an opportunity for Laurie and Amy to connect as a couple (dancing-wise, at least!) because staying in tune with each other to switch things up is key. Practicing years ago at home would certainly have helped, and would have made it easier for the pair to dance well together than to dance as gracefully with other guests at the ball.

Tarantula, or Tarantella

Finally, let's end with a quick note about the "tarantula" Amy would rather be dancing at the beginning of the ball. In both the Matteson (2016; p497) and Shealy (2013; p479) annotated editions of Little Women, there is a note that Amy is incorrectly using "tarantula" where she means "tarantella" (a Sicilian folk dance). I expected this to be a quick note about the presence (or lack) of tarantellas in mid-19th century Parisian ballrooms...but I actually found the word "tarantula" in multiple dance manuals, including Howe's! The best description of a tarantula I found is from The amateur's vademecum: A practical treatise on the art of dancing by E. Reilley, published in Philadelphia in 1870:

"But no dance has so singular a history respecting its origin as the national dance of the Neapolitans, called the Tarantula...Love and pleasure are conspicuous throughout this dance. Each motion, each gesture, is made with the most voluptuous gracefulness. Animated by the accompanying mandolins, tamborines and castenets, the woman tries, by her rapidity and liveliness, to excite the love of her partner, who, in his turn, endeavors to charm her with his agility, elegance, and demonstrations of tenderness. The two dancers unite, separate, return, fly into each other's arms, again bound away, and in their different gestures alternately exhibit love, coquetry and inconstancy. The eye of the spectator is incessantly diverted with the variety of sentiments which they express; nor can anything be more pleasing than their picturesque groups and evolutions. Sometimes they hold each other's hands, the man kneels down, whilst the woman dances round him, then again he rises; again she starts from him, and he eagerly pursues. Thus their whole dance is but assault and defence [sic], and defeat or victory appear equally their object."

However, the plot thickens. I did find one dance manual that refers to the Italian dance as a tarantella and not a tarantula: Coulon's hand-book; containing all the last new and fashionable dances, published in London in 1866 and 1873 (expanded). Coulon writes:

"To dance the Tarantella, however, in our circles as they dance it at Naples would be impossible, and, therefore, when Madame Michau introduced it in London in 1845 she made a selection of about eight steps or figures, that have had great success among the higher classes here."

Here is where I admit that I've never done either the traditional Italian tarantella or the European ballroom version described by Coulon. Looking at his instructions, the ballroom version is a dance for individual couples (in open and closed positions), which seems pretty different from at least the modern versions of the tarantella that I've seen. Someday hopefully I'll get to try reconstructing this, and then I will add a video!

But for now, I'm not sure that using the term "tarantula" is Amy making a mistake. As it appears to be a somewhat common term for referring to the folk dance (in American sources at least), Alcott may just be using the term she's seen. Or it could be even more intentional, to differentiate the Italian folk dance from the ballroom dance "la tarantella" her readers may have seen or heard about.

|

| tarantella or tarantula? |

That's it for this week! Next up is likely a break from the dancing and a return to costuming for a bit, since I've actually been sewing. But if you're enjoying these posts, there are more to come!

Happy New Year to all!

*While Aunt March funds Amy's trip abroad, she doesn't actually go--instead, Aunt Carrol and cousin Florence are Amy's companions

**here, "Noah Webster" refers to Webster's Dictionary

***Another note on terminology: we tend to refer to each of these sections as "figures", but that's a bit confusing because the individual patterns that make up a figure are also called figures. In the dance manuals, they referred to the sections of the quadrille as numbers or by names (for example, the third section of the Prince Imperial quadrille in the video above is called "la corbeille"). I've abandoned Howe for a second in favor of The Prompter: Containing full descriptions of all the quadrilles, German cotillons, etc. by William De Garbo (New York, 1865) as his discussions of quadrille mechanics are a lot more detailed. De Garbo explains the makeup of quadrilles:

"A Quadrille is one Number of Figures. Two or more Figures constitute a Number: as in 1st No. Quadrille Francaise, “Right and Left” is a figure; “Balancé” is the next figure; “Ladies Chain” the next; and “Balancé” the last: altogether, these figures constitute a Number. Five Numbers usually constitute what is termed “a set of Quadrilles;” as the “Lancers Quadrilles,” “Caledonian Quadrilles,” “Le Prince Imperial Quadrilles,” etc. It is common to designate Numbers as Figures,— i.e ., instead of 1st No., 2d No., &c., they are sometimes called 1st Fig., 2d Fig., &c. The former definitions are preferable; the term “Numbers” according with the five Numbers or different pieces of music set to the Quadrilles. Figures accord with the strains of music."(emphasis mine.)

No comments:

Post a Comment