This is just a pickled limes blog now.

(Not really, obviously. I just posted about sewing and there's more sewing coming up. But the flood gates are open and I will not apologize for the pickled lime content.)

When I embarked on the

Pickled Limes Project of 2020, I started a post about the type of lime that would have been used for the pickled limes eaten by Amy March in

Little Women. But I sort of lost steam on it, partially because I couldn't get anything but a few large limes (Persian/Bearss limes, I think) at the grocery store. (It was 2020, after all. I was honestly thrilled that I found some decent limes of any kind at all.) So I went about my experiments with what I could get, and this particular thread of the research has been tugging on my brain ever since.

This spring when I was invited to a gathering of Alcott friends, I decided it was the perfect excuse to try making pickled limes again. This time with the correct lime variety! And (spoiler alert): it turns out the limes make all the difference.

|

| map of the West Indies c.1860 |

As I mentioned in my previous research write-ups, a lot of remaining documentation about pickled limes as they were eaten in New England comes from trade commission reports and import tax lists. This isn't very helpful in knowing what pickled limes taste like, but it's useful for understanding where they came from and how they got to Boston. So let's start with that process. The journey from the lime tree to Amy March's hand in 1862 would likely have been:

1. Limes are picked on a plantation in the Leeward Islands - likely Dominica or Montserrat - between June and September.

2. Ripe limes are placed in casks, which are then filled with seawater. The seawater is changed frequently until the limes are "properly pickled".

3. The casks of limes in saltwater brine are sealed and shipped to Boston.

4? The pickled limes are purchased in Boston by grocers, who move them from the saltwater into vinegar.

5? The grocers sell the limes individually for a penny each*.

The big question mark on those last points is because I do have references that describe pickled limes being brined in vinegar, so I'm not positive if there was a step after shipment to Boston where the saltwater-brined limes were put into vinegar. But references to "preparing" pickled limes for sale does lead me to think this kind of preparation by the grocer makes sense. These references come from grocers' manuals such as The Grocer's Companion and Merchant's Handbook by the New England Grocer Office (Boston; 1883):

"LIME -- A fruit resembling a miniature lemon. It is best known to commerce when prepared and sold as 'pickled limes'."

That "prepared and sold as" bit is what makes me think at least sometimes the limes did go into vinegar (or sugar!). I also do have references explicitly to pickled limes being sold in vinegar. For example, this description of pickled limes comes from The Housekeeper's Guide to Preserved Meats, Fruits, Vegetables, etc. (London; 1889):

"LIMES WEST INDIA PICKLED

West India limes can be obtained pickled in vinegar in bottles. They are very similar to pickled lemons and of course are somewhat acid. ...[In Germany] they are sometimes eaten at the commencement of dinner as an appetiser in the same way as pickled gherkins cucumbers etc.

LIMES IN SYRUP Limes when premixed served in syrup form a very delicious sweet. They are also very wholesome when fresh fruit cannot be obtained. In long sea voyages they form an excellent dessert dish and they also possess considerable cooling properties."

But we've already discussed steps 2 - 4 in previous posts. Today is about step one: the limes and the picking of them.

The West Indies and Lime Plantations in 1862

In the mid-19th century, Great Britain occupied much of the Caribbean. To understand the region I'm going to focus on Montserrat, one of the two islands mentioned as a major lime exporter in period records, because I could find the most documentation on the lime trade there. Beginning in the late 1600s, enslaved Africans were brought to Montserrat and other islands in the region by British and French companies to work sugar and indigo plantations. By 1810, there were reportedly 7,000 enslaved people living on the island. In 1834, the Abolition of Slavery Act abolished slavery in Montserrat (although we should note that it did not abolish slavery everywhere in the British empire, and the people on Montserrat were still living under Imperial rule)**. As sugar plantations became less profitable, many companies abandoned their properties on the island.

Fast forward to the founding of the Sturge Montserrat Company in 1857. The Montserrat Company purchased abandoned plantations and then turned the land around for profit - some of the land they subdivided and sold to settlers, while other plots were kept whole and used as farmland for lime cultivation. Mrs. John Edward Sturge, the director's wife, described this land as:

"No lovelier sight could be seen than these orchards when the trees are laden with their bright fruit, the air being pervaded with the fragrance of the blossom."

The Montserrat Company later used the same practices to cultivate and export limes from the island of Dominica as well. From the two islands, their exports included "green limes" (whole fruits packaged in paper, like oranges), casked pickled limes, lime essential oil, and raw and concentrated lime juice. While limes are used in some Caribbean dishes, Montserrat Company reports say that "there are no local buyers in any of these islands"; instead, everything grown was shipped to America or England.

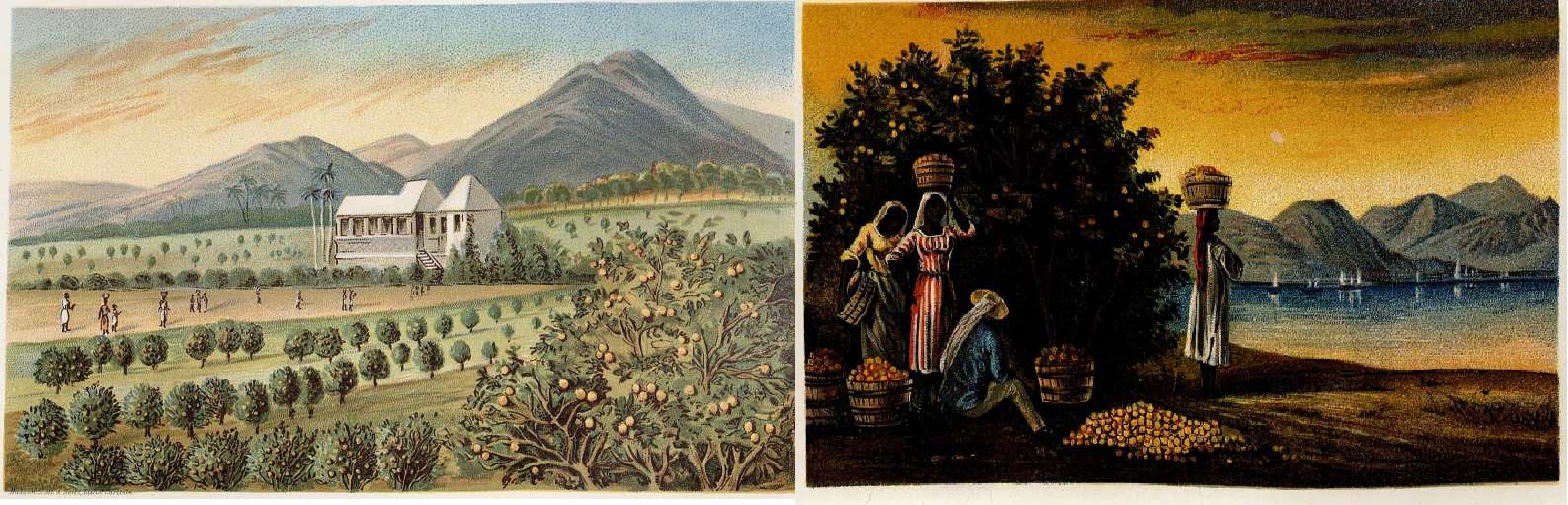

|

| Illustrations of lime cultivation and harvesting in Montserrat (via) |

West Indian Limes

While lime plantations were aimed at export, the trees they cultivated were native to the Caribbean. In period sources they are described as small, round, and yellow. These, I am pretty sure, are West Indian limes, or citrus aurantifolia, now more commonly known as Mexican limes or Key limes. The same type of lime appears to have been found in all of these countries at the time, based on descriptions of fruit imports to New York written by the Montserrat Company. So it makes sense to me that what I now call a Key lime is the same fruit being cultivated for export in the Caribbean at the time.

A later Montserrat Company report from 1913 also describes the flavor and popularity of these limes:

"It is generally conceded by all who have become accustomed to the flavour of the lime that this fruit far surpasses the lemon in the delicacy of its flavour, and it is well known that when these fruits are grown together for household purposes as often happens in the West Indies the lemon is only used when there are no limes on the trees."

So if West Indian (aka Key) Limes are small and mildly flavored, it stands to reason that they'd be much easier to eat whole when pickled - or for a schoolroom of girls to surreptitiously suck on.

And as I mentioned at the beginning, they do indeed make much better pickled limes. I think this is a combined result of a sweeter fruit and a thinner, more delicate skin.

And don't worry - since tasting has already happened, you'll be hearing more about the process and the final results in great detail.

Notes:

*Why a penny? That's my best guess based on the money Meg gives Amy for her lime debt (25 cents) and how many limes she buys (25). Here's the passage:

"'Why, I owe at least a dozen pickled limes, and I can’t pay them, you know, till I have money...'

'How much will pay them off and restore your credit?' asked Meg, taking out her purse.

'A quarter would more than do it, and leave a few cents over for a treat for you. Don’t you like limes?'

'Not much. You may have my share. Here’s the money. Make it last as long as you can, for it isn’t very plenty, you know.'

...Next day Amy was rather late at school, but could not resist the temptation of displaying, with pardonable pride, a moist brown-paper parcel, before she consigned it to the inmost recesses of her desk. During the next few minutes the rumor that Amy March had got twenty-four delicious limes (she ate one on the way) and was going to treat"