When the 2017 miniseries aired, there was one scene in particular that made me pause and re-wind during the first episode. That scene was the first party of the book, where Jo meets Laurie.

|

| screenshot of the scene in Little Women on PBS, at about 16:17 in episode 1 |

Dancing was a frequent activity in the Alcott household, and we know from the family's letters (as well as letters written by their friends) that they loved to dance and attended dances often (although in every letter Louisa insists she doesn't know the steps, which I am greatly amused by). It seems only fitting that a few key scenes in Little Women take place at dances.

|

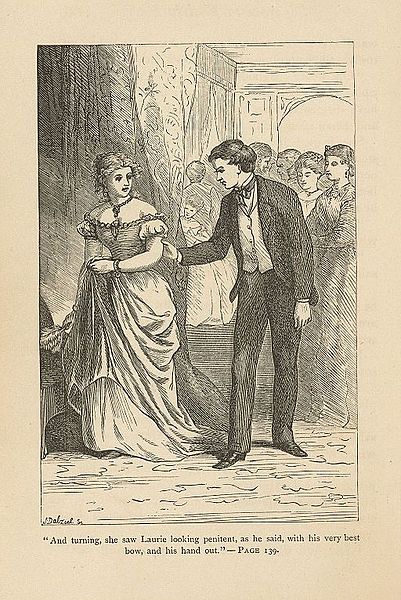

| Illustration by May Alcott, 1869 (from Houghton Library) |

Let's get started with a little bit of dancing, shall we?

A couple of important things:

1. I apologize in advance for the often not-great dance footage...I don't have a ton of videos available! We did a couple of big 1860s performances several years ago, and recently created a series of overviews so that's the footage I have to work from. (shameless plug: see dancing live in technicolor by coming to a ball sometime!)

2. All of the dance information I'll be discussing in these posts comes from primary sources. Alcott letters and novel texts are of course the big ones for my particular selections, but what about the dancing? Let's start there.

Dance Descriptions and Dance Manuals

In the mid-19th century, dance teachers commonly published manuals on ball etiquette, basic dance posture and steps, and instructions for popular dances of the day. These books were a resource for learning new dances, and updated editions were often released only a few years apart. For the dances I'll describe, I'm primarily using publications by Elias Howe. He was a New England dancing master, and his dance manuals Howe's complete ball-room handbook and American dancing master, and ball-room prompter were both published in Boston, MA in 1858 and 1862 respectively. Since the real-life Alcotts and fictional Marches were all in New England for much of their lives I think these are appropriate for our discussion. (Yes, I know we'll hit Europe in the latter half of the novel--I'll discuss that when we hit those chapters.)

Dancing was also sometimes discussed in the press, both in coverage of particular events or in sharing a particularly hot new trend. We'll touch on both of these sources.

To set the mood, here is Howe's introduction to his 1858 dance manual:

"There is no scene in which pleasure reigns more triumphantly than in the ball-room...The music rising with its voluptuous swell, the elegant attitudes and airy evolutions of graceful forms, the mirth in every step, unite to give to the spirits a buoyancy, to the heart a gayety, and to the passions a warmth, unequalled by any other species of amusement."

Elements of mid-19th century Dancing

In the mid-19th century, there were three main types of dance setups*:

-contra (or country) dances: couples are arranged in rows (sometimes straight, sometimes in a circle) and dance with each other, progressing throughout the dance to new couples

-quadrilles: in America, these are usually done in squares of four couples (one on each side), and each part of the dance is repeated for the different people dancing

-round (or "couple") dances: one couple dances together around the ballroom; these are what most people now think of when they think of "ballroom dances"

The takeaway here is that there were many different kinds of configurations in which you might dance while attending a ball. And it was a lot to keep track of! So it's no wonder Louisa insists she never knows the steps.

Another important term to know is figure, which is the term for the different parts of a dance. Figures appear across many dances, which is kind of nice--if you know the "ladies chain" figure, you can get through it even if the dance you're doing is totally new. Since most contra dances and quadrilles are many of the same figures in different orders, it's much easier to pick up new dances than you might expect once you're comfortable with the bits...and also sometimes a lot harder to keep them all straight in your head.

The photo above is a figure from the Prince Imperial Quadrille--notice the square? Here's an example of a contra dance, called Soldiers Joy:

and a couple dance (this is a bit of polka from a choreography, which starts about 1:05 and ends at 1:30):

All of these styles would be on the same program during an evening, so you'd have a lot of options for different things to do. Here's an example dance list from Lincoln's inaugural ball in 1861, courtesy of dance historian Barbara Pugliese:

So a mid-19th century person would have learned a basic vocabulary of dance elements, including figures (patterns that make up a dance), steps (how you move your feet), and variations (specific patterns of steps used in turning dances). Then they would have a repertoire of dances they knew completely (so the figures in order, etc.) that might change over time depending on trends and preferences among their social circle. Like spoken language a dance vocabulary can be combined in many ways, but if you've got the basics you can usually pick the rest up as you go. And like language, dancing has evolved over time--so while a lot of the terms may sound familiar to modern ballroom or contra dancers, the execution is different.

Some Other Notes

(or the things that didn't get their own section, but are worth noting)

Alright, I think I'll leave it here. Do you feel prepared for the ballroom? Next time we're jumping in with the dances named in Little Women, so stay tuned!

*I'm keeping things pretty simple, so pardon the generalizations.

The photo above is a figure from the Prince Imperial Quadrille--notice the square? Here's an example of a contra dance, called Soldiers Joy:

and a couple dance (this is a bit of polka from a choreography, which starts about 1:05 and ends at 1:30):

All of these styles would be on the same program during an evening, so you'd have a lot of options for different things to do. Here's an example dance list from Lincoln's inaugural ball in 1861, courtesy of dance historian Barbara Pugliese:

|

| note: "lancers" is a particular genre of quadrille, with a really neat evolution...it's still done as a folk dance in several places today, including Denmark and the Caribbean. I actually attended a week-long dance program where the theme was lancers, just to give you a sense of the scope of stuff we could touch on. I'm only scratching the surface here! |

Some Other Notes

(or the things that didn't get their own section, but are worth noting)

- Like modern social activities, dancing was enjoyed by people regardless of gender. While parts in a dance are defined as the "gentleman's part" and the "lady's part", there are many recorded instances of women dancing with women and men dancing with men. I will use the terms gentlemen and ladies throughout these posts to discuss the parts of a dance, but I wanted to acknowledge up front that even in the 1860s, that wasn't a hard-and-fast rule.

- On a similar note, partners typically changed every dance, so you would dance with many people in a single evening. Howe states it is good manners for married couples to only dance together once or twice.

- Dance cards or dance programs were popular for larger events, and often had spots to write in the name of your partner for that dance. Howe notes that it is impolite to ask someone to dance too far in advance--so the mad rush we might imagine to fill a dance card with partners right at the beginning of a ball is somewhat counter to the actual likely pace of the evening.

- Positions have changed over time, and the proper closed hold in the 1860s was low and rounded (different from modern ballroom form).

- The goal was (and still is!) to be sociable--smiling and enjoying the evening was more important than getting everything perfectly right. I think that's especially true for evenings described by Louisa, with good friends and cozy parlors full of lively people.

|

| illustration from Howe, 1858 |

*I'm keeping things pretty simple, so pardon the generalizations.